Product Pricing (4/4): Setting the Price

Even with a solid strategy, setting the price has many wrinkles

Thanks for reading the ProductFix newsletter. This is the final part of a four-part series on product pricing. This week I discuss setting the price.

As always, if you find value in reading this please give me some love by liking and sharing with others.

📰 Article👍🏼 Recommendations🍺 Overtime📰Article

Setting the Price

Usually, when people think of product pricing, the first thing they want to consider is the price point. Now that I have tackled the pricing team, models, and strategy this article finally tackles that key issue.

Let’s look at what goes into setting an optimal price and some of the key terms used in pricing.

This is the fourth article in a four-part series on product pricing. The first three articles covered who should be on a Pricing Team, core Pricing Models, defining your Pricing Strategy.

List Price

The standard offering price of your product is referred to as the List Price. This is the Price that you will generally communicate to potential buyers of your product and acts as an anchor for all subsequent negotiations, including discounts.

This should be the starting point of all negotiations with prospects.

For example, let’s say the list price for a unit of your software is $100,000 per year and you offer a 10% discount on a 3-year agreement. When the customer agrees to the 3-year term, they will be paying a Total Discounted Price of $270,000 against a Total List Price of $300,000.

Annual Contract Value (ACV) is the actual contracted price to be paid per annum. In the example above the ACV = $270,000. The ACV is the relevant metric that SaaS providers keenly track as part of managing growth.

It is important to always communicate the List Price to the customer. Add-ons and renewal fees should always be driven off the List Price and this is how you anchor on the value you believe your product delivers. Even if you choose to discount subsequent sales you need to be consistent about the value messaging.

It is also important to be consistent with your List Prices and Discounts offered to the market as this helps run a smooth operation and it simplifies minimizes financial accounting and audit risk.

Calculating and Setting List Price

As discussed in the Pricing Models article, there are two primary approaches to setting List Price for enterprise software. The first is Competitive Pricing Models and the second is Value-Based Pricing Models.

Competitive Pricing

Perform competitive analysis and set your prices based on a combination of your competitor pricing, your product competitiveness, and your pricing strategy. Frequently, you will vary off of these but they form the baseline for how you set List Prices.

Value-Based Pricing

Defining the List Price is much less objective and requires greater creativity in value-based approaches. There are multiple techniques that can be applied to quantify value and acceptable pricing ranges.

Top-Down Value Estimation - The most common technique for enterprise software is to estimate the value your product potentially delivers. Typically, we look at the following:

Incremental Revenue Generation: How much more revenue can the customer expect to capture if they use our product? Examples include increased lead generation, higher NPS, higher price points, and quality improvements.

Cost Savings: How much can a customer save if they use our product? This can be derived from direct financial savings, reduction in headcount, a more efficient workforce, faster processes, etc.

Risk Reduction: Reducing any number of risks to the customer is the most complex to value. Risks may be operational, financial, reputational, regulatory, customer attribution, and even criminal. Specific examples include regulatory compliance, cybersecurity threat reduction, insider abuse, drug safety, process failure, system downtime, and poor talent recruitment.

We estimate the value the company applies to a particular category of problem-based on their total spend to address it, the impact to the business, or the opportunity cost if they fail to take it. Based on this value, we can then estimate how much a customer would be willing to pay to achieve that value.

The willingness to pay for a solution is always a fraction of the total value of the problem or need addressed times some confidence factor. As your product matures and demonstrates greater confidence through referrals and testimonials, you can generally capture a greater percentage of the value.

Example: Expense Reporting Fraud Prevention software. Let’s say that we can estimate the typical company loses $50,000 per year in fraudulent employee expenses. If we believe that our software can reduce this by 80%, there is a potential $40,000 annual benefit. Customers then will pay less than $40,000 to account for the risk of being wrong and the costs associated with achieving it. Therefore, it would be wise to set your List Price at $10,000-$15,000 per year.

Van Westendorp’s Price Sensitivity Meter - A great methodology for setting value-based pricing, usually reserved for consumer goods. Through the use of 4 key survey questions, you can understand acceptable pricing to customers.

At what price would the product be priced so high you would not consider buying it? (Too expensive)

At what price would the product be priced so low you question its quality? (Too cheap)

At what price would the product start getting too expensive, that would require some thought before buying it? (Expensive)

At what price would the product be priced low enough you would consider it a great bargain? (Good Value)

Based on the responses to this survey, along with your pricing strategy, you can decide where on the spectrum of acceptable pricing your product should fit.

Conjoint Pricing Analysis - A survey-based statistical technique used for value-based pricing to determine prices customers are willing to pay for various combinations of features/attributes.

Conjoint Analysis is really powerful for pricing commodities like TVs or mobile service packages to understand optimal feature/price mix but is very infrequently used for pricing enterprise software.

Market Feedback and Learning

After initially setting your product pricing, it is critical to continuously assess market feedback from win-loss reports, analyst feedback, and competitive research to determine if the List Pricing makes sense.

Pricing Feedback to Gather:

If you provide a freemium product use surveys to ask why users are not converting to paid tiers.

If you provide a freemium product use surveys to ask customers that do convert to a paid tier, why the made the decision.

If prospects repeatedly choose competitor products and cite price as a factor, have a follow-up conversation.

If you never lose opportunities over price, it may be that you are priced too low for the value you provide.

As you collect this pricing intelligence, it does not all demand immediate action. However, it is important to update pricing regularly based on new lessons from the market.

Perceived value versus perceived price

A critical point to understand is that, while you may do detailed research to assess the value of your product to your customers - this is not the same value they always perceive. If you have testimonials of other customers saving $1m per year once going live, your prospect may still view their situation as unique and assess the value of only $500,000 in savings.

Secondly, the price of your product is not the List Price. For the customer, the perceived price includes other expenses like training and switching costs from legacy technology. In fact, for many applications, these costs may dwarf the List Price of your software. This is the Perceived Price to your customer.

In both cases, the Perceived Value and Perceived Price, are critical to understanding when selling and defining a pricing strategy. As a product team, your job is to continuously increase the ratio of perceived value over perceived price through a combination of improvements to the product, effective marketing, and pricing strategy.

Example: E-Commerce Platform. Consider an e-commerce platform that provides all the inventory management, shopping cart, purchasing, payment processing, and shipment capabilities a small business needs. Let’s assume you sell this turnkey e-commerce package for $10,000/year.

For brick and mortar local shops going online for the first time, they perceive this as a $10,000/year price. However, for all prospects already using a competitive platform or a home-grown solution, they will perceive a much higher first-year price due to transition costs.

If converting competitor customers to your platform is key then you will want to improve the product to minimize the switching costs OR consider some incentive pricing for the first year to reduce the perceived price. Such discounts should not be targeted at greenfield customers.

Psychological pricing

In consumer goods, psychological pricing is very commonly discussed related to the .99 at the end of prices. However, it also applies to enterprise products. Consider products that publish clear pricing online. There are a few ways psychological pricing plays a role.

Conveying a Premium Product. If you have a product that can easily be compared with others in the same category, providing a higher price point than your competition signals that yours is of higher value. Customers will expect better quality and a more mature, complete offering.

Conveying a Bargain Product. If your product compares to others in the same category, but you price it lower, this conveys that it is a bargain product. Customers will infer lower quality, fewer features, and other characteristics that reduce their value.

Closely Matching Prices. If you have multiple tiers of pricing, as do your competitors, the price points that are closest to your piers will define the product variations for customers to compare.

These situations arise regardless of whether you start with competitive or value-based pricing models. Whether or not these are your intentions when pricing these are the outcomes that can arise when pricing is readily available within a defined category.

As such, it is important to continuously watch for competitor pricing moves. When they set or adjust pricing, this impacts how the market will view your products as well.

Discount Policy

When you are small and just getting started, oftentimes executive management and product leadership are all actively involved in enterprise software pricing tactics. As you begin to grow your business or a product within a larger organization it is important to remove obstacles and friction from the selling process. A discount policy does this.

Just as Product Teams like to be given a product strategy and then the autonomy to execute, Sales Executives like the same autonomy to close deals. A Discount Policy provides them with the flexibility to drive business without asking for a lot of permission.

A common approach is to provide Sales Execs with the ability to discount up to 10% without approval. Larger discounts up to 20% require Sales VP approval.

By deciding in advance what discounting is allowed, it can be defined in a manner that fits with the business and product strategy. For example, new products may have no discounts or minimal allowed. New customers may have greater allowed discounts. Some products with tricky OEM constraints may have a more limited discount.

The keys here are that, for every product, sales must understand up-front the List Price and their ability to Discount to be most effective while supporting business objectives. If they do not have this you are either in an extremely low volume market or they will (rightly) complain a lot about red tape and friction.

Product Bundling and Add-ons

Frequently, enterprise software products are offered standalone or as a group of related products. Add-on products, by contrast have no value unless they are coupled with a base product.

In order to remove obstacles in the sales process, it is a good practice to establish the List Price for bundles of standalone and add-on products that may be commonly purchased together.

When purchased together, versus standalone, the customer will typically benefit from an additional bundling discount. The vendor is benefiting substantially from increased customer lock-in, while the customer stands to derive greater value from integrated offerings and working with a single vendor.

Example ERP Suite: Finance and HR base products with add-ons for Applicant Tracking and Payroll Management. 10% discount for the ERP Suite.

Pricing Discrimination

As discussed in the Pricing Models topic of Value-Based Pricing, most enterprise software requires consideration for how to differentiate, a.k.a. discriminate, pricing to align with variation in perceived value.

Since you are selling a single product, you can’t set a flat price without losing opportunities with smaller customers or, worse, leaving money on the table with larger customers. To thread this needle, you must find a proxy for the anticipated value. Further, you want to define an approach that if the customer value grows over time, you, as the vendor, can capture some of the increase in value.

Example: HR software. Your research indicates that customers associate value as it relates to scaling its employee headcount. So you will want to use Employee count as the proxy for discriminating pricing.

The most basic form this takes is:

$50/employee/year

Such pricing is straightforward and provides both the vendor and customer with clear costs to plan around. As the customer organization grows the vendor will benefit in a proportional manner.

The first variation we might see is that, if you as a vendor, want to focus on larger organizations as part of your strategy a minimum price point can be set.

$5000/year up to 25 employees

$50/year for each additional employee

A second variation is that customers view diminishing value as their organization scales. So while $50/employee makes sense for 50 employees it does not with 200. So you create price breakpoints.

$5000/year/employee up to 25 employees

$50/year/employee from 26-50 employees

$35/year/employee from 51-200 employees

$20/year/employee from 201-1000 employees

$12/year/employee above 1000 employees

Separate breakpoints, as in the example, work well and give customers the ability to plan for their growth in administrative costs as their workforce grows. It is best to model the breakpoints over commonly understood milestones in the proxy metric tied to growth in your customer’s business.

Packaging Tiers

Similar to pricing discrimination is the concept of package tiers. Sometimes these have labels like Bronze > Silver > Gold or Pro > Team > Enterprise. Tiers differ from pricing discrimination in that they tend to provide a different set of features and value at each tier.

Attaching Price Points to the Value distinguished at each tier is critical to effective contract negotiations. By staying firm on such tiers, if procurement insists on better pricing, your sales team has the simple solution of agreeing the lower price in exchange for providing a lower value product tier.

Sure you can have Microsoft 365 for $5/user/month but then you won’t get the ability to work with Word, Excel, and Powerpoint offline using desktop tools your employees are most familiar with.

Transparency in Pricing

It is clear, that many software companies today are leaning toward greater pricing transparency. For straightforward products, this makes tremendous sense, especially in highly competitive commodity-like categories.

Many enterprise products do not provide publicly available list prices. For some vendors, this is due to competitive fears. Assuming that once you publish your prices you will have competitors using that against you or it may remove your negotiating power with customers.

The primary reason that enterprise software vendors do not publish pricing today is that they use value-based pricing models which can become very complicated as you add up multiple products and add-ons in a suite.

As more and more vendors move to publish transparently this becomes a tricky problem for those that do not. Yet, communicating complicated pricing approaches often creates friction in the sales process and can sometimes turn away prospective customers.

The dynamics of your particular product category and the culture of your organization will dictate when to ultimately share pricing details. However, whenever you share pricing, be absolutely clear on the value your product delivers. It is always a best practice to share the value promise before the price to acquire it.

Conclusion

Product Pricing is an incredibly important aspect of defining a product, bringing it to market, and supporting business objectives. Setting the Price is one key step but it should be done within the confines of a clear Pricing Strategy with the support of a cross-functional Pricing Team.

This article touches on some key concepts used in setting pricing but there is much more in practice. In future articles, I will return to Product Pricing with more examples from the market and tackle some of the advanced contracting issues that arise surrounding Product Pricing.

As Product Managers, we need to be involved and ideally leading these discussions. Getting a handle on these concepts will elevate you professionally and your product commercially.

👍🏼Recommendations

Book: Creating Great Teams: How Self-Selection Lets People Excel by Sandy Mamoli. This books delves into the thought-provoking concept of letting engineers decide which teams they want to be on.

Podcast: Pricing is Positioning by Paul Klein. Paul’s podcast is geared toward pricing professional services work not enterprise software. Still, I think there is a lot to be gained in some of the strategies he advocates.

🍺Overtime

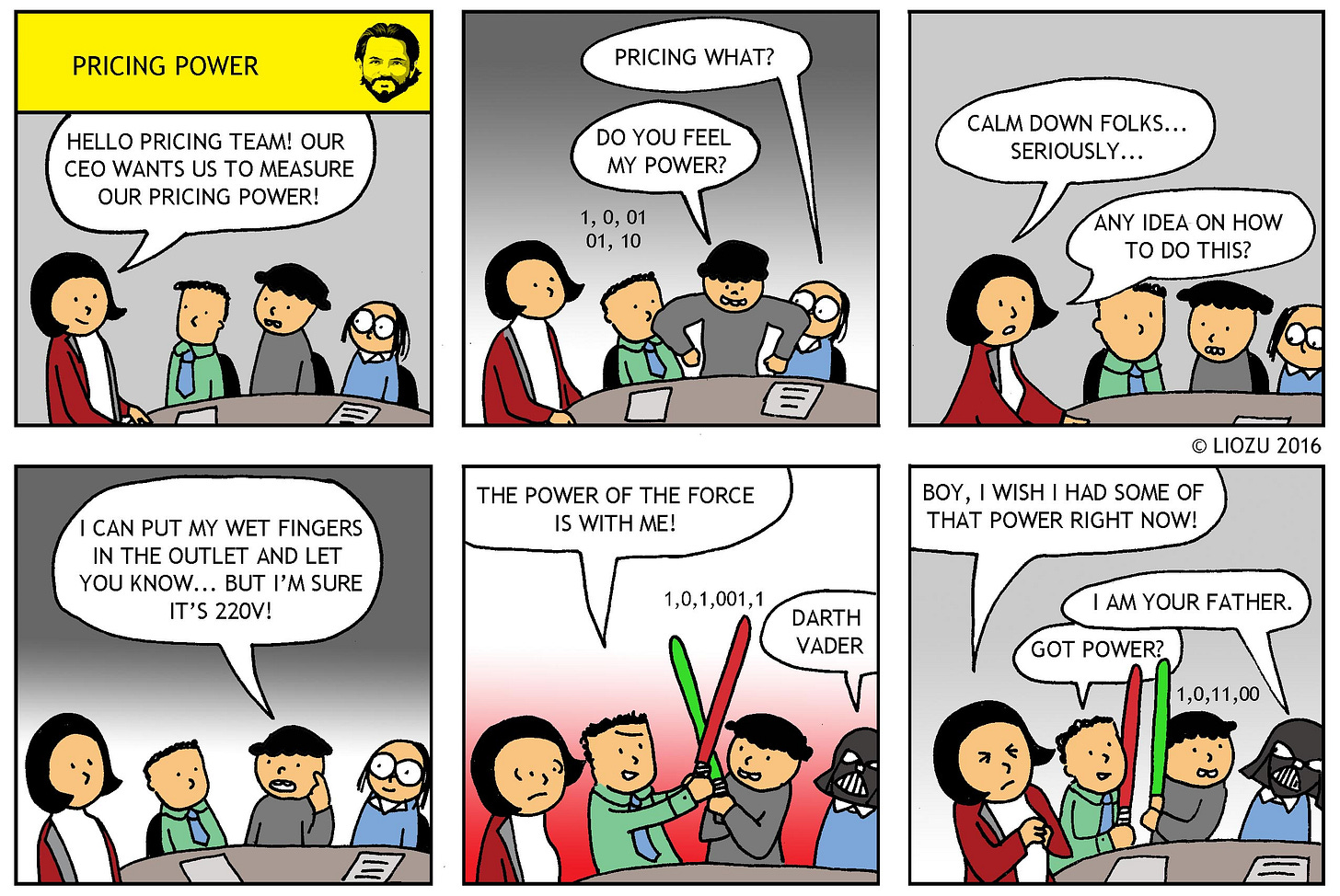

Credit: Stephan Liozu

Don’t be shy. Please hit the heart and comment to share your feedback. Beyond that, I coach product leaders to take advantage of best practices and challenge their own perspectives. If that sounds useful, take action now, and schedule an appointment.

An excellent summary -- thank you for posting this. I like a lot of point you make here. The biggest challenge, at least in my experience, both in my corporate past and now, as someone who's building his own content business is perceived value versus perceived price. It's especially tough one when you are new player (or an established one, but going into a new space). In these case it's all about changing perception.

Thank you for the great series, it was insightful to read all the articles. A suggestion would be if you also cater to an article of what factors should a PM look at when pricing a new feature. For example, how shall a PM at an airline aggregator price a "refund on cancellation" policy. Again, thanks for covering pricing in this detail.